Today is my 11th wedding anniversary. We aren’t able to travel anywhere or do any of things we’d normally choose to celebrate, like checking out a new coffee shop or visiting an old house, so I’ve been thinking back on our trip to London last year. It was our first overseas trip together, and one we’d been looking forward to taking for several years.

We stayed at The Blackbird in Earl’s Court, an ale-and-pie house and boutique hotel run by a 175-year-old pub company. The room was gorgeous and comfortable, the staff was wonderfully accommodating of our need to stash our luggage before check-in, and our stay included a full English breakfast each morning.

The Blackbird is also a short walk to the Earl’s Court tube station, and a longer but no less pleasant walk to Shaukat, famed home of affordable Liberty London prints. I treated myself to two three-meter cuts of Tana lawn in coordinating colorways to make matching button-up shirts for me and Justin. I’m waiting for cooler weather to embark on the process of fitting shirts before I cut into this precious meterage.

As enthusiastic museum-goers, we were spoilt for choice, but I ruled that the Victoria & Albert Museum and the British Museum were our must-sees for this visit. I’d had my heart set on seeing the Elgin Marbles since I’d first read Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” and I was not disappointed—in fact, I was not at all prepared for the scale of the stonework, despite knowing full well these carvings adorned the pediments and other high places of the Parthenon and were intended to be seen from dozens of feet away at minimum.

I acknowledge that my ability to witness and enjoy the (more aptly named) Parthenon Marbles with relative ease, in an English-speaking country with customs and cultural expectations not dissimilar from my own, is a privilege predicated on an unresolved, and to a certain degree unacknowledged, crime. I wholeheartedly believe the Marbles are the rightful legal, historical, and cultural property of Greece and its people, and that they should be returned to Greece to be reunited with the remaining marbles.

I admit that my discomfort about the British Museum’s continued possession of the Marbles was outweighed by my desire to experience art of exceptional significance, to stand where Keats once stood and to maybe feel what he felt looking at them. Seeing the Marbles has reinforced for me in a more tangible way that they ought to be returned, and I can at least say that we opted not to financially support the British Museum while we visited. Was I wrong? Perhaps. I can only say that I’m trying my best, and I hope one day to view the Marbles again when they’ve been restored to their rightful home.

Right, enough of that—on to less weighty things!

We splurged on two stage shows while we were there: Hamilton at the Victoria Palace Theatre…

…and A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Shakespeare’s Globe.

Unfortunately I don’t have any photos from the latter show, and I can’t tell you how much I wish I did, because it was wild. The aesthetic was a mash-up of Mexican-inspired pinatas and early 90s neon streetwear. The cast was visibly diverse, the pop culture asides were hilarious, and my new favorite stage gag of all time is watching a man throw down an inflatable mattress as a form of protest, and then later looking on as a woman who feels spurned by him kicks open the pressure valve, causing him to sink to the floor as the mattress slowly, sadly deflates. Pure gold.

Other highlights for us included:

Taking in the view from the London Eye

Walking through Westminster Abbey (though we could only snap photos of the exterior) and pausing at the memorial stones of C.S. Lewis, Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning, the Brontë sisters, Lord Tennyson, and my beloved Romantic poets Keats, Byron, Coleridge, Shelley, Wordsworth, and Clare, among many others.

Touring the Tower of London and traversing Tower Bridge

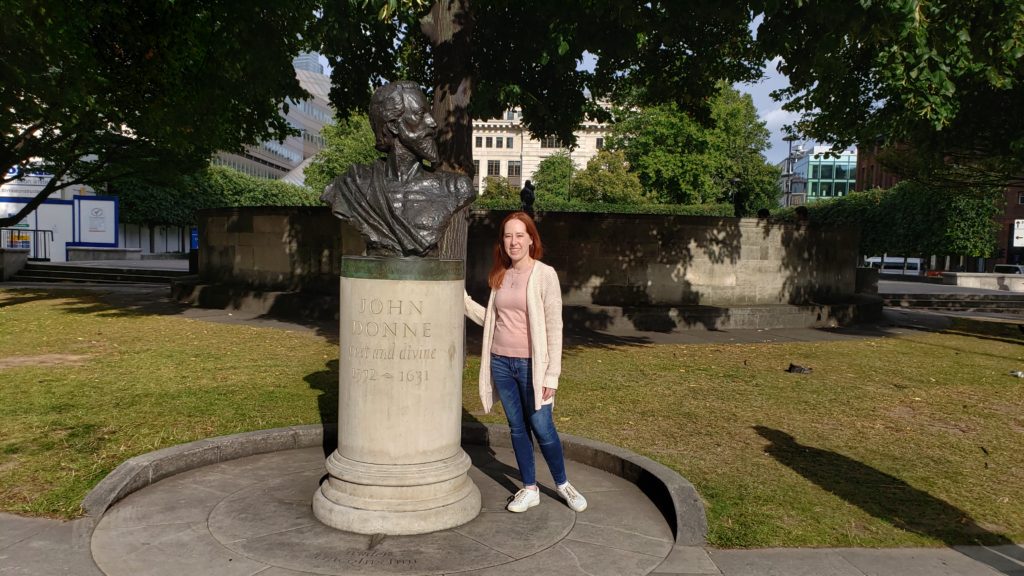

Stopping outside St. Paul’s Cathedral to honor another of my favorite poets, John Donne

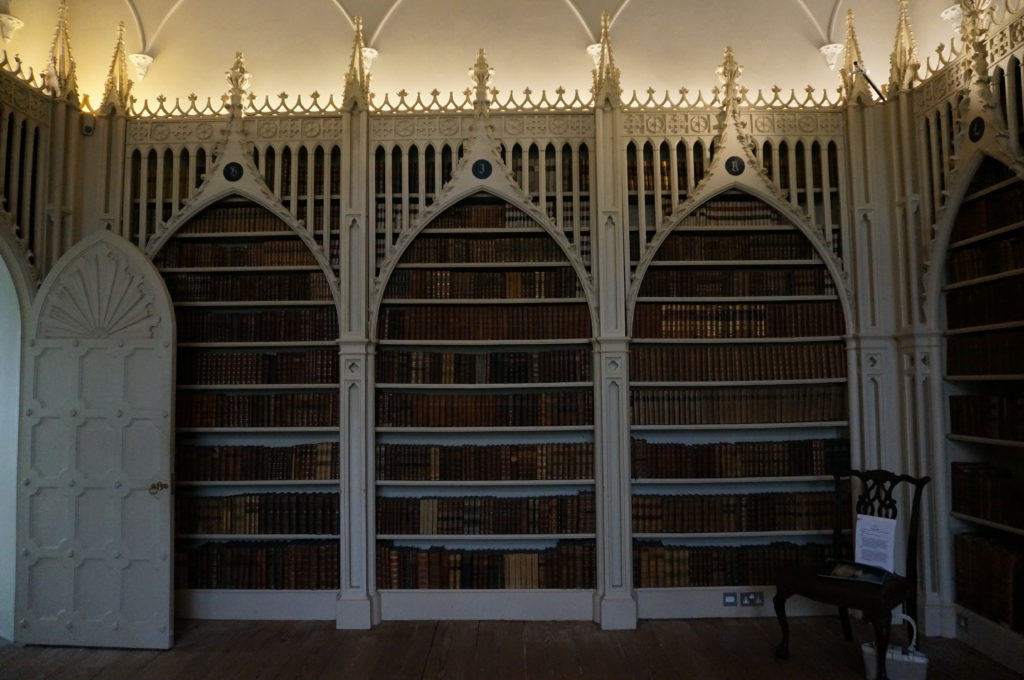

Spending several hours at Strawberry Hill House, home of Horace Walpole, the father of Gothic literature and arguably the first person to use Gothic architectural elements in a private dwelling (in a manner later dubbed neo-Gothic)

I could probably devote another entire post to the all of the excellent food we ate during our five-day trip, but I’ve indulged in enough non-craft content already. Instead, let’s chat about a little hobby tourism!

In addition to Shaukat, we visited Liberty London, which I was surprised and delighted to find is also a Rowan Yarns flagship store. I ended up passing on both fabric yardage and yarn there, but did pick up a fine cotton floral bandana/handkerchief.

But for a proper fabric and yarn crawl—planned using these handy maps from The Fold Line—we headed out to Islington. We slipped into Sew Over It shortly before they closed, securing a couple of their house patterns, a peachy dotted chiffon for a future blouse, a mug, and some chocolate bars. Then we went to Ray Stitch, where I dithered over fabric, talked myself out of buying more patterns, and settled on a tiny cache of buttons and enamel pins.

Our last stop was Loop, and we were warned when we came in the door that they were also closing soon. I had just enough time to do a lap of their first and second floors before the lovely, long-suffering shop folk put the screws to me to make a decision. I hadn’t come with a particular plan in mind, but I was determined to leave with something of uniquely U.K. provenance.

After scanning a few labels and hefting a few yarns, I chose this teal-y blue Hayton 4ply from Eden Cottage Yarns. It’s a merino cashmere nylon blend with a semi-solid appearance, slightly fuzzy halo, and next-to-skin softness.

It turned out to be an excellent match for the Luna Viridis pattern from Hilary Smith Callis. I’d previously purchased the pattern to use up a skein of Cascade Heritage Silk reclaimed from a failed scarf, but the smooth, solid-colored yarn didn’t wow me. The Hayton, however, is just right.

If I needed further proof that it was a perfect match, the pattern is named for the moon, and the yarn’s colorway is “Tide.”

I made one deliberate change to the pattern, lengthening it to use all but a few yards of the yarn, and one accidental change, which was to misread which motif was supposed to be used as a spacer between larger pattern sections. If you’re curious, you can read more about that in my notes on Ravelry.

After my experience knitting Magical Realism, I was dubious of another in-the-round circular shawl construction. But this one begins like a triangular shawl before being joined in the round, and I found it a pleasure to knit. In fact, I think I might like to make more like this one, since I enjoy one-skein projects but don’t love having to fuss with loose ends that come free. (In my experience, not all bandana-style scarves come unwrapped, but if they come undone once, they’ll keep coming undone every 15 minutes for the rest of the day.)

Indulging in hobby tourism is one of the things I love about traveling with Justin, although I’m ashamed to admit I have souvenir skeins from earlier trips that are languishing in my stash, waiting for the right project. I suppose if I can’t visit any new yarn stores, I might just have to “revisit” yarn stores of days past via those patient skeins.