While I was visiting my family for Thanksgiving, I had the experience of witnessing a time-worn idiom come to life, when my mom approached me with hat in hand to ask for my knitting expertise. The very literal hat in question was a light grey, slouchy, slightly fuzzy beanie with alternating bands of plain and textured knitting, the crown of which had started to come undone. She had picked up the hat to wear when walking the dog, and she admitted that though it was nothing particularly special, she would nevertheless be sad to lose it to unraveling. She asked if I would be willing to take it home and try to repair it, which I readily agreed to do.

Fortunately for the hat (and my nerves), once I carefully unpicked the tangle of loops at the top of the hat, I discovered the situation was not as dire as I feared. The crown had not been cinched shut with the tail of the working yarn, but had instead been secured with a separate strand of yarn, and it was this strand only that had broken. None of the yarn used in the knitting itself was damaged—no snags or severed plies to fuss with—which meant it was a relatively simple task to latch up the few dropped stitches and then close the top of the hat with a strand of stash yarn in a similar weight and color.

Since I knew I’d see my parents again at Christmastime, I had the hat in my possession for a couple of weeks, during which time it occurred to me that I had the power to do more than simply keep a humble accessory from meeting an untimely demise: I could, in fact, template the cherished item and ensure that it lived on through an infinite number of iterations, should the owner so desire. Or, at the very least, I could create a copy, doubling my mom’s sartorial choices and prolonging the life of the original hat. Which, as far as I’m concerned, is a close second behind hat-based immortality.

To make my copy, I started by taking some flat measurements of the height from brim to crown, the height of the ribbing, and the height of a pattern repeat. The stockinette and reverse stockinette portions were easy to identify, but I had a slightly harder time with the other texture, which sort of resembles ribbing if the knits were squatter and more pronounced and there were no purls between them. After some searching and comparison, I came to the conclusion that it was probably fisherman’s rib. Whereas the original hat had been worked flat and then seamed, I think seamless hats are one of the ways handknitting distinguishes itself as superior to machine knitting, so I found instructions for knitting fisherman’s rib in the round and was off.

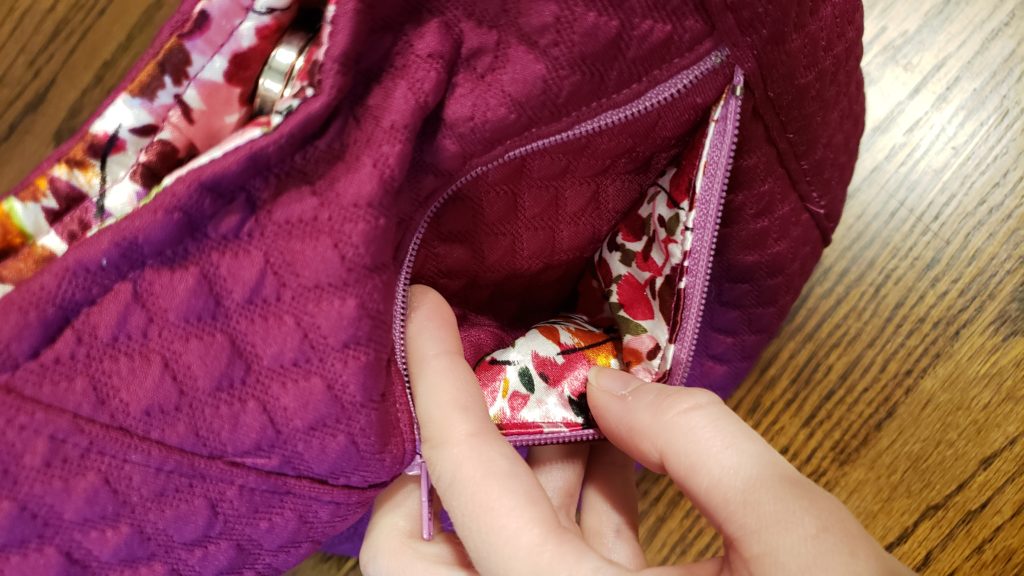

The yarn is Malabrigo Rios; the colorway is Natural. The recipe for this hat can be found on my Ravelry project page. Contrary to the care note I sent my mom (hi Mom!), it is, in fact, machine washable, so long as it’s placed in a garment bag on a cold, gentle cycle. It still has to be laid flat to dry, but being wool, it doesn’t need to be washed all that often. I enjoyed working with the yarn so much that I used it again for another hat and also a sweater—more on them soon.

I wish I’d had the common sense to take a photo of the original so I could show you both hats side-by-side and you could be impressed by what a good match they are, but I think we all know by now that that kind of forethought isn’t my specialty. Just picture the hat above in light grey and a little fuzzier. Pretty similar, eh?